Retirement Planning With Taxes

MoneyBee includes simplified estimates of your federal and state taxes, premium tax credits and RMD in each year after retirement.

Note that neither our calculator, nor our firm, MyVal Center, provides tax advice. Any tax-related projections done by MoneyBee should be viewed as an approximate allowance for taxes in retirement and not as tax advice, a tax estimate or a final tax calculation.

For most Americans, taxes are significantly simpler in retirement than during our working careers. This doesn't mean, however, that you can ignore them altogether when planning for retirement. You will continue to pay state and federal taxes after you retire, and they will still be an important part of your financial life. However, many of the tax rules that will apply to you during retirement are very different from the tax rules that apply to your employment income. Therefore, you can neither ignore taxes after retirement nor simply estimate them based on your current taxes.

Social Security benefits

The good news is that only a fraction of your Social Security benefit will be subject to federal taxes. No more than 85% of your benefits can be taxed, and many people pay no federal tax on them at all. Where you stand in that spectrum will depend on the level of your benefits, your marital status, and the amount of any other taxable income.

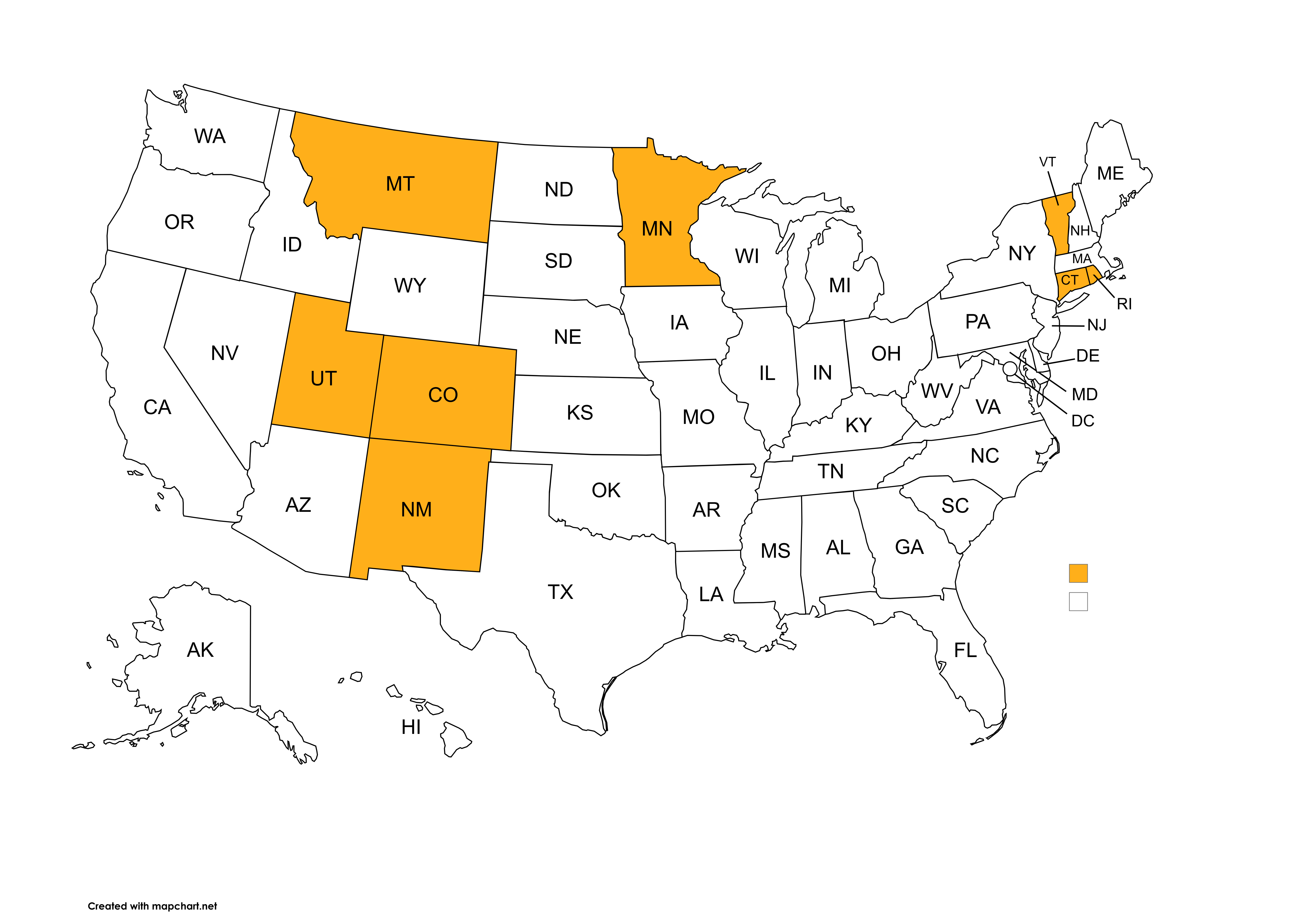

In addition, chances are you won't pay any state taxes on your Social Security benefits. Most states do not tax Social Security benefits, including high-tax states like California and Hawaii. Of course, some states, like Texas and Florida, have no income tax to begin with. Starting with 2026, only the following states highlighted in gold may tax some of your Social Security benefit:

Even these states generally follow the federal rules, which means that only a fraction of your Social Security benefit will be taxed, if any. Some of these states add additional credits on top of the federal rules, which means that an even smaller portion of your benefit may be taxed.

Withdrawals from retirement accounts

When you retire, a large portion of your income will come from your savings. But you need to be careful, because the taxes you will pay on these withdrawals will depend on the type of account you are drawing from:

Pre-tax retirement accounts (such as 401(k), 403(b) or similar employer plans, traditional IRAs, SEP IRAs, or rollover IRAs) - Since you never paid taxes on this money, your entire withdrawal will be subject to regular income tax. In addition, if you withdraw money prior to age 59.5, you will also have to pay a 10% penalty on the amount withdrawn. To make things even more complicated, once you reach age 72, you will have to withdraw a minimum amount each year (called the "required minimum distribution"). This means that you may need to withdraw more than you need and get taxed on it.

Roth IRAs - Since your contributions to these accounts have already been taxed, you don't have to pay tax when you withdraw them. The big selling point of Roth IRAs is that you also don't have to pay tax on the interest you have earned! However, if you make a withdrawal prior to age 59.5, your earned interest may get taxed depending on the amount of the withdrawal.

Regular after-tax savings - These are your regular savings, outside of any special tax-advantaged retirement accounts. Since this money has already been taxed, there will be no further taxes when you make withdrawals. However, the portion of that withdrawal that is attributable to interest earned is taxable.

Capital gain from a home sale

Many Americans choose to sell their home in expensive urban areas after they retire and move to a less expensive area. Downsizing is a great way to fund your retirement, as it may generate a significant amount of cash. However, Uncle Sam (and your state) will want their share of the proceeds from the sale, too. There are two ways in which the tax on these proceeds may differ from regular employment income:

Lower tax rates: For federal tax purposes, it will be taxed at long-term capital gain tax rates (up to 20%), which may be significantly lower than regular income tax rates (up to 37%).

Large deductions: If the home was your primary residence, you can deduct $500,000 from the capital gain if married, or $250,000 if single. While this deduction is for federal tax purposes, it reduces your adjusted gross income, so you may effectively get the same deduction for state tax purposes as well.

Moving to another state

Many people consider moving to a state with a lower cost-of-living after retirement to make their savings stretch further. If you choose this strategy, it is crucial to consider the tax implications, too. In fact, some people move to a different state when they retire precisely to save on taxes. This decision would make it tricky to estimate your post-retirement taxes from your pre-retirement taxes.

Mortgage interest

Your mortgage payments might be the same amount every month, but in the eyes of the federal and state tax authorities they are not. If you have a fixed-rate mortgage, the interest portion of your payment (and the corresponding tax deduction) will be smaller every month. When your mortgage is paid off, the tax deduction will disappear completely. So while your mortgage payments remain fixed, your tax payments may actually increase. It is important that your retirement plan takes this into account.

Is estimating your taxes in retirement even possible?

Obviously, it would be unrealistic and impractical to perform an exact tax calculation for each year in retirement. Even if you did know every relevant detail in advance, would you really want to fill in a TurboTax-type questionnaire for each of your 30 years in retirement?

However, a reasonable tax approximation at both state and federal levels is indeed achievable by making some conservative simplifying assumptions, and without overwhelming users with technical questions.

At a minimum, your retirement calculator should reflect the current tax brackets for federal and state purposes, increased with inflation. Then it can apply the basic tax rules for the items most common in retirement, as discussed above:

Social Security benefits

Withdrawals from retirement accounts

Capital gains from home sales

Mortgage interest

Employment income during retirement

That should cover most bases for most people. Your calculator may need to make some simplifying assumptions by ignoring some of the "bells and whistles" surrounding these rules. Some simplifications may be acceptable for retirement planning purposes since very long financial projections - such as planning decades of retirement - always involve a fair amount of uncertainty.

But how do we decide what to ignore? One reasonable approach may be to ignore tax rules if they meet all three of these criteria:

1) It's a tax reduction whenever it applies. It's safer to ignore rules that reduce your taxes than to ignore rules that add to your taxes.

2) Its impact is relatively small in most cases. Even if a rule is a tax reduction, it would be unreasonable to ignore a major tax perk such as the fact that your state doesn't tax Social Security benefits.

3) It requires many additional inputs from the user. Even if a rule results in a relatively small tax reduction, why ignore it if it doesn't require any additional inputs from the user and is relatively easy to code?

For example, the special credits applied by states that tax Social Security benefits meet all three of these criteria and may be safe to ignore. These credits lower your taxes, they are unlikely to have a significant impact for most people, and they can potentially require a lot of additional questions for you.

Note that it's impossible to guarantee that a rule will always have a small impact for everyone. This is why full disclosure of any simplifications is so important. This gives you, or your tax adviser, a chance to determine if any tax rules that have been ignored may be too conservative in your particular case.

Conclusions

Taxes are a tricky area for retirement calculators. Some discernment is needed in deciding which rules to include and which to ignore.

At the same time, your taxes will be very different in retirement and likely change significantly over time. Any reasonable approximation would be far more accurate than ignoring taxes or assuming some ballpark figure based on your current taxes. Such reasonable approximation is indeed achievable by using carefully selected criteria for deciding what tax rules can be safely ignored. The goal is to remain conservative enough to avoid unpleasant surprises while not overwhelming you with too many technical questions.